“Over the last year and a half, there has been some fundamental change, where people are looking for something else out of the jobs … better hours, better working conditions,” said Andy Challenger, senior vice president of Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

In August alone, more than 4 million people voluntarily quit their jobs, the highest number recorded by the Labor Department since it started tracking the figure more than 20 years ago.

To stem the rising tide of worker discontent, companies are offering record-high wages, sweetened benefits packages, and hefty sign-on bonuses in an effort to retain and woo workers.

Paul Osterman, who teaches human resources and management at the MIT Sloan School of Management, said the labor shortage situation should, in theory, be good for people looking for work, since it gives them an upper hand. That’s why it is troubling that since the start of the pandemic, more than 4.3 million people have stopped looking for work. But while “people are being much more choosy” now, he said not everyone can remain out of the workforce forever.

“It’s a race between people’s fear of going back to work and a need to pay the bills,” he said.

Here’s a look at seven types of jobs that have markedly declined in popularity over the last year and a half, why they may never be the same again, and what that might mean for consumers.

Restaurant workers

What’s going on? Walk by most restaurants, and there’s likely a “Now Hiring” sign on the door or in a window. Hosts, servers, cooks, and bartenders are all in high demand.

There was an exodus of workers from the industry during the pandemic following COVID-19 shutdowns and restrictions that led to closures and layoffs. As the economy reopened, restaurants that survived have struggled to ramp up to full capacity, resulting in reduced hours and seating, limited menus, and longer waits for service. In many restaurants, servers are doing double duty as bartenders or as hosts. And it’s not uncommon for owners to work in the kitchen during the busiest hours.

A National Restaurant Association survey conducted in September found that nearly 80 percent of restaurants said they are understaffed.

The upshot: Restaurants are adapting to dealing with a leaner workforce. In some cases, that means expanding kitchen areas so that there is more room for to-go and delivery orders and less space for customers to sit. For others, it means investing in technology, such as QR codes to replace the role of servers, or in the case of Sweetgreen, buying robots from MIT that will make the chain’s signature salads.

Baristas

What’s going on? With so many office employees working from home ― and likely never going back in on a full-time basis ― coffee shops near their lonely buildings have cut back on hours, removed seating areas, converted to takeout-only, or closed.

Meanwhile, employees at Pavement Coffeehouse and Darwin’s Ltd. in the Boston area have moved to unionize for better working conditions amid a nation reckoning within the industry that’s even reached industry giant Starbucks.

The upshot: The days of a barista knowing your name may be waning. The two largest coffee chains operating in Massachusetts are replacing some human interaction with tech, perhaps making the process of getting a cup of coffee more efficient, but no doubt less personable. Dunkin’ just opened a “Dunkin’ Digital” store on Beacon Street in Boston where customers order through a touchscreen kiosk or an app. And Starbucks is planning to open a pick-up and delivery-only store in Cambridge.

Supermarket/retail cashiers

What’s going on? Despite inflation, consumers are increasingly spending money at stores, and major retailers ― including Costco, Walmart, and Target ― are reacting by raising wages so they have enough employees to meet the demand. The Washington Post reported that the average pay for restaurant and grocery workers has surpassed $15 nationally, according to Labor Department data.

But even with more perks and fatter paychecks, companies say they are still having trouble reaching hiring goals. As a result, some are taking steps to keep from losing people already on staff. Target, for example, said it will hire fewer seasonal employees than last year and pay its current workers more.

“Usually we are deep into the temporary holiday hiring phase,” said Challenger. “Some companies aren’t even announcing temporary hires, they are just trying to backfill all these permanent positions that they haven’t been able to staff.”

The upshot: Stores are starting to put more emphasis on self-checkout and curbside pickup. They also are closing traditional checkout aisles during hours when staffing is short, resulting in longer waits that could drive more consumers to online shopping.

Truck drivers

What’s going on? The trucking industry has long faced a shortage of drivers, but the pandemic added another layer of concern. The workforce, which skews older, was at high risk for COVID-19, but tasked with traveling around the country at the height of the pandemic, helping to restock store shelves wiped clean by panic buying while keeping up with a surge in online ordering.

A confluence of factors pushed some drivers to retire early or pursue different careers. Now, the industry is struggling to attract new drivers as it tries to keep up with a global supply-chain nightmare that shows no signs of abating.

The upshot: Truck driving doesn’t pay badly ― an average of more than $61,000 in Massachusetts, according the job site ZipRecruiter ― but the profession demands serious tradeoffs, including weeks on the road, isolation, and tight quarters. It’s not exactly entry-level work, either, since it requires a commercial driver’s license.

Warehouse and logistics

What’s going on? Similar to brick and mortar retail businesses, companies involved in the end of the supply chain are trying to beef up their staffing, too.

UPS, eager to hire 100,000 seasonal workers, said some candidates will receive a job offer within 30 minutes of submitting an application. Amazon announced last week that it is hiring 1,500 seasonal workers in Massachusetts as part of a 150,000-person national hiring spree. The jobs pay $18 an hour and include sign-on bonuses of up to $3,000.

In a September earnings call, FedEx executives said labor shortages increased costs by $450 million, mostly because of higher wages, hiring incentives, and the money spent trying to meet shipping deadlines with fewer people. And FedEx still has 90,000 positions to fill ahead of the holiday shopping season.

The upshot: Challenger said the “bonus bonanza” could have unintended consequences, pulling people from other companies, instead of targeting the millions of people that left the workforce during the pandemic.

“I’ve heard at least anecdotally that people are coming into a job, waiting for their sign-on bonus, and then going to the [business] across the street and collecting that one,” he said.

And for those looking for work processing or delivering packages, the primary qualification this year may be having a pulse.

Uber/Lyft drivers

What’s going on? The pandemic was not kind to Uber and Lyft drivers, as people hunkered down at home instead of hailing rides to work, restaurants, and events. Even those people who did venture out were more likely to take their own car. Conversely, many drivers were not keen on the idea of interacting with a string of strangers in a small enclosed space. Demand for the service has returned, but not all drivers have.

Harry Campbell, founder of industry blog The Rideshare Guy — and a gig driver himself — said that when the ride-hailing business flatlined, many drivers signed up to work for booming food delivery services instead, and haven’t switched back.

“You put a lot less miles on your vehicle with [food] delivery, since people are ordering from local restaurants instead of calling 20 to 30 mile rides,” he said.

And with gasoline prices at their highest level in years, putting fewer miles on a car has a direct effect on a driver’s bottom line. According to the latest national data from AAA, drivers are paying $17 more on average to fill up their tanks than they did at this time last year.

“If gas prices are up and your earnings stay constant … you literally make less money,” Campbell said.

The upshot: Uber and Lyft have been spending millions of dollars to attract more drivers over the past few months, but in their latest earnings calls, executives said there’s still a long way to go.

Uber chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi said in August that in major cities, “prices and wait times remain above our comfort levels.” When asked about whether riders may switch to alternative modes of transportation, Lyft chief financial officer Brian Roberts said its customers have been “relatively patient with the less than ideal prices and service levels that they face industrywide.”

Hotel workers

What’s going on? The labor situation is slightly different when it comes to hotel workers, said Carlos Aramayo, president of Unite Here Local 26, the local hospitality workers union. Because of the lack of events, conventions, and business travel, hotels are not scrambling to hire back all the workers they employed pre-pandemic.

About 80 percent of local union members are back at work, Aramayo said, but most are working only about 65 percent of the hours they used to, largely because not all hotel amenities ― including room service and hotel bars ― have returned. Hotel occupancy hovered at about 40 to 50 percent over the summer.

But Aramayo said hotels in areas such as South Florida, where the economic recovery has been more robust, are pulling out all the stops to hire people quickly, offering incentives such as wage increases and referral bonuses. It could be a sign of what’s to come in Boston.

“We have not seen that panic in this market; there are still people waiting to get their jobs back,” he said. “But once we hit 100 percent occupancy, I don’t know if there will be enough people.”

A possible tip of the iceberg is the already tight market for cooks. Aramayo said the new Omni Boston Hotel at the Seaport had to offer pay at above union wages to fill positions before it opened last month.

The upshot: Although Aramayo said workers’ union contracts prevent an outright replacement of human jobs with technology, he’s seen more moves to head in that direction. He’s skeptical that getting rid of hotel perks — and employees — would be good for the industry in the long run.

“The hotel industry distinguishes itself from Airbnb and VRBO by saying ‘we offer a whole range of amenities,’” he said. “If industry makes a lot of cuts …I think a lot of travelers will say, ‘Airbnb is cheaper, why would I stay here?’”

In other words, hotel guests are going to want clean towels and refreshed bottles of shampoo every day, not just when they make a special request for such basics.

Anissa Gardizy can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @anissagardizy8.

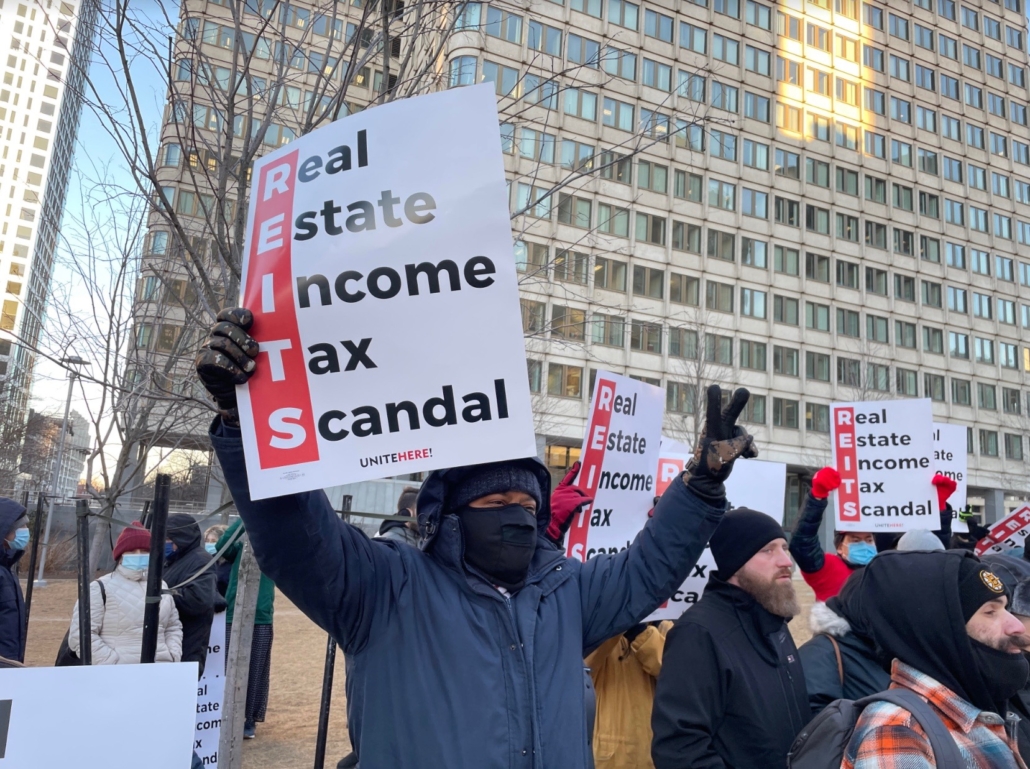

Boston, MA — 100 hotel workers and members of the hospitality workers’ union, UNITE HERE Local 26, along with workers in 21 cities across the U.S., organized a National Day of Action on Thursday to shine a light on the “shadow boss” hotel owners they say are driving cuts to jobs and services in the hospitality industry. Workers will rally outside the IRS building in Government center and will be joined by State Senator Lydia Edwards and Boston City Councilor Ed Flynn.

Boston, MA — 100 hotel workers and members of the hospitality workers’ union, UNITE HERE Local 26, along with workers in 21 cities across the U.S., organized a National Day of Action on Thursday to shine a light on the “shadow boss” hotel owners they say are driving cuts to jobs and services in the hospitality industry. Workers will rally outside the IRS building in Government center and will be joined by State Senator Lydia Edwards and Boston City Councilor Ed Flynn.

A small group of hotel union workers in red-and-black T-shirts reading “Come Back Stronger” gathered outside a closed-for-construction Copley Square Hotel Thursday, asking that the hotel’s owners reopen the storied property and reinstate their jobs.

A small group of hotel union workers in red-and-black T-shirts reading “Come Back Stronger” gathered outside a closed-for-construction Copley Square Hotel Thursday, asking that the hotel’s owners reopen the storied property and reinstate their jobs.

With more than

With more than

At the Revere Hotel Boston Common, excitement for the Boston Marathon was building all week. Runners were checking in. Employees decorated the lobby in yellow and blue. The Rebel’s Guild restaurant kitchen was planning a Sunday night pasta dinner.

At the Revere Hotel Boston Common, excitement for the Boston Marathon was building all week. Runners were checking in. Employees decorated the lobby in yellow and blue. The Rebel’s Guild restaurant kitchen was planning a Sunday night pasta dinner.