Hotel workers hoping for pandemic job protections

MARYANN SILVA HAS worked for 19 years as a full-time banquet server at the Ritz-Carlton hotel on Boston Common. The 63-year-old Lynn resident sets up and serves food to guests for weddings, meetings, birthday parties, and corporate events.

She was “temporarily” laid off in March when COVID-19 hit and the hotel closed. But the property still hasn’t reopened. Silva remains on unemployment benefits and has no idea if she will get her job back. Silva is divorced with no children and takes care of her 97-year-old mother. She had been earning $60,000 a year. Now, she has turned in her leased car for a less expensive one and worries about losing her home if she can’t continue to pay her mortgage.

“It’s so uncertain,” Silva said. “You’re working, at least you know you’re out there making a living for yourself and your family.”

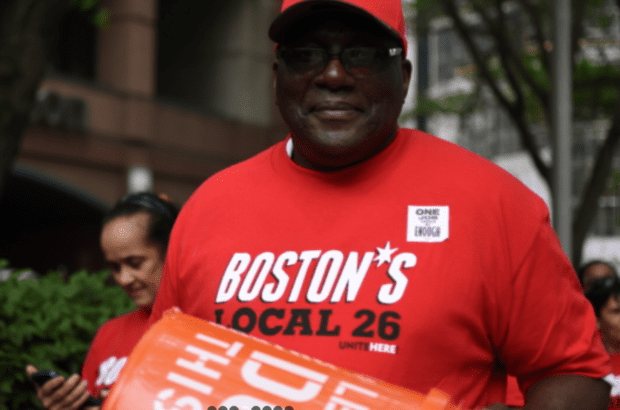

An amendment that will be considered as part of the House budget debate this week could give laid-off workers like Silva a small measure of hope. It would require hotel workers laid off due to the pandemic the right to be rehired into their old jobs if those jobs are brought back. The amendment was introduced by Rep. Marjorie Decker, a Cambridge Democrat, and pushed for by the union UNITE Here Local 26, which represents Boston area hotel workers.

For Silva, the knowledge that her job is protected “would take a lot of stress off of my shoulders,” she said.

UNITE HERE Local 26 president Carlos Aramayo said, “What people are looking for is some peace of mind that if and when the job is recreated, they will have the first chance to take that job.”

The head of the Massachusetts Lodging Association did not return a call for comment. The national American Hotel and Lodging Association has generally opposed these types of policies, arguing that they place an additional burden on employers struggling to recover from the pandemic.

The amendment would not mandate anything, but would let individual municipalities adopt a “right to recall” policy. Under that policy, a hotel that lays off a worker due to the pandemic and then reinstates that job any time during a two-year period would have to offer the laid off worker their old job back. There would be civil fines for noncompliance.

Decker said hospitality workers have been hit hard by COVID-19 “and if we’re going to really be able to have a strong recovery in our economy we have to make sure the workers who helped build this economy and are most experienced are given the shortest path back to their jobs.”

Similar policies have been adopted on a municipal level in several California cities, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, and Oakland, although a statewide right to recall bill was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom. Newsom, a Democrat, said it would create an onerous burden on employers. A right to recall policy was also adopted earlier this month in Providence, Rhode Island.

Aramayo said the policy is necessary because of how hard the pandemic hit workers in the hospitality sector.

According to state labor statistics, there were more than 380,000 Massachusetts leisure and hospitality jobs in January. That dropped to below 140,000 in April and has bounced back only partially, to 242,000 jobs by September.

“Thousands of hospitality workers in the hotel industry were put out of work and continue to be out of work because the industry relies heavily on not just tourism, but also large-scale events that are not scheduled to happen anytime soon,” Aramayo said.

Aramayo said many industry workers are older, female, immigrant and have little formal education. “These are not people who are going to be easily retrained for other jobs that would be equivalent in terms of income and standard of living,” he said. He worries that hotels will try to cut costs by replacing more experienced workers who have higher salaries with younger, cheaper workers.

Aramayo said of 4,500 Boston hotel industry workers his union represents, only 400 to 500 are back at work. UNITE HERE workers do have a contract that requires managers to recall workers for up to a year after a temporary layoff. The amendment would extend that to two years and would also cover non-union workers.