Terminated Marriott Copley staff’s new jobs show a working class being forced further down the economic ladder

Beatriz Torres almost made it. She worked for 23 years at the Boston Marriott Copley Place, cleaning and serving food to VIPs in the concierge lounge, and planned to stay for two more so she would qualify for free stays at Marriott hotels for life.

But last September, Torres lost her job, along with half the hotel’s staff, when business plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The property is slowly coming back to life, but Torres, 70, isn’t part of it; nor are most of the 229 hourly employees terminated along with her. Torres now works at Starbucks at Logan Airport, making roughly $7 an hour less than she did at the Marriott.

Torres was among scores of employees, many of them immigrants, forced out after working at the city’s second largest hotel for years — decades, in some cases — making upward of $20 an hour, enough for some of them to buy houses, send children to college, and support family members back home. Nearly a year later, many have found new jobs, but often at reduced wages, without the steady hours and retirement benefits they had before. At the same time, Marriott Copley has contracted out its sports bar and restaurant, Champions, to the Yard House, which is paying far less for some jobs than the hotel did.

From the outset, the pandemic has wreaked havoc on the country’s lower-wage workforce, particularly those in the service industry. And as the dust settles, it’s becoming clear that many corporations seeking to recover losses are doing so on the backs of their workers, pushing them out, and down the economic ladder, as they look to cut labor costs permanently.

Torres, who is originally from Mexico, said her meager savings are gone after being out of work for 16 months, as are her dreams of spending her retirement visiting family in Texas and Spain. So far, she’s managed to pay her bills and hold on to the room she rents from an El Salvadoran family in Everett, but she’s fearful for her future.

“It’s like a nightmare that I’m living,” Torres said. “What is going to happen to me?”

Marriott Copley did not respond to requests for comment.

Like service workers around the country, the terminated hotel employees have been caught in the crosshairs of the COVID-19 crisis.

Immigrant women with limited English skills and no higher education who worked in food service and accommodation suffered more job losses during the pandemic than any other group in Massachusetts, according to a report released in March by the Workforce Solutions Group, a statewide advocacy coalition.

Hotels in Boston, where more than two-thirds of hospitality workers are people of color, are still reeling from the pandemic. As of July, hotel room revenues in the area were down more than 70 percent year-to-date compared to 2019, according to Pinnacle Advisory Group — the slowest recovery after San Francisco and New York among large markets.

This is a critical moment for the industry, said Chip Rogers, president of the American Hotel & Lodging Association. As travel continues to languish, the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of workers could be at risk without federal aid, he said, noting that in Boston, properties have received little to no pandemic relief.

Across Massachusetts, employment in the hospitality and leisure sector was down 20 percent in July compared to two years ago, according to Pinnacle, by far the hardest hit industry in the state.

Hmad Birali, a former dishwasher at the Marriott Copley, recently landed another hospitality job, as a housekeeper at a small hotel in Brookline. But he’s now making just $15 an hour, with no 401(k) match and no guarantee of full-time hours. He recently applied for several jobs at the Marriott Copley, where postings for Yard House dishwashers are listed at $17-$20 an hour — less than the $25 an hour he was making at the Marriott, but more than he’s making now. So far, there’s been no response.

Birali, 51, is worried that he won’t be able to afford the rent on the one-bedroom apartment he shares with his wife in Revere, or to send money to his mother and 15-year-old son in Morocco.

“They used me,” said Birali, speaking in Arabic through a translator, noting that he worked nights for five years, never called in sick, and did any job managers asked of him. “In the end they just threw us in the street.”

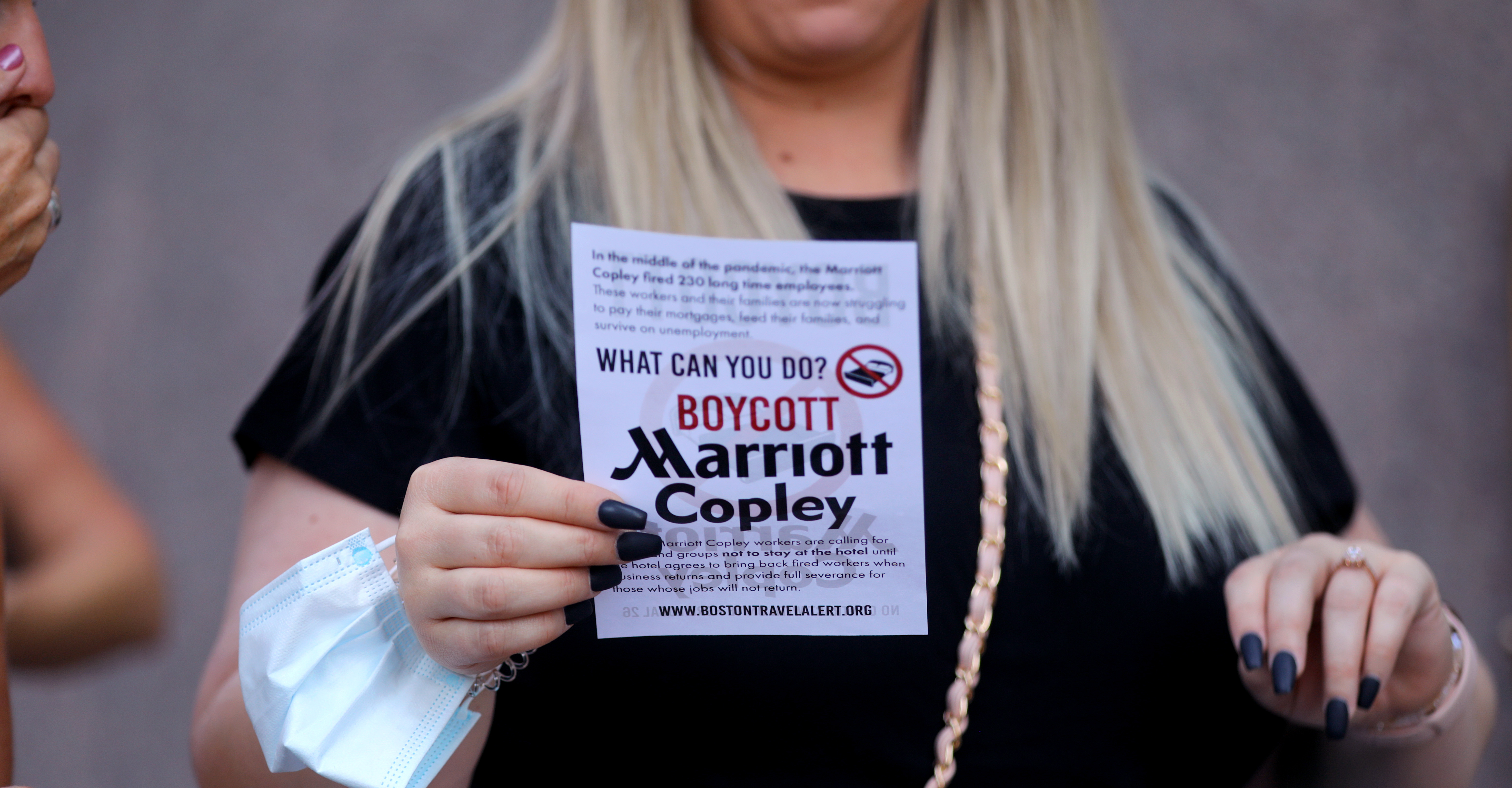

Last year, essential workers were hailed as heroes, said Darlene Lombos, head of the Greater Boston Labor Council, and now, with corporate profits squeezed or nonexistent, they’re expendable — that is, an expense that can be cut. On Labor Day, the council held a rally in front of the Marriott Copley to condemn what Lombos called “the throwing away of Black and brown workers who are actually risking their lives to save ours and keep us going as a society.”

Payroll is the industry’s biggest expense, said Sebastian Colella, a Boston-based vice president at Pinnacle Advisory Group, and considering the robust staffing levels and decent wages at many properties, reining in labor costs is the first thing they’re going to look at. And those changes could be permanent, he said: “That’s something that might stick.

Indeed, the chief executive of Host Hotels & Resorts, which owns the Marriott Copley, told investors in earnings calls that the company viewed the pandemic as “an opportunity to redefine the hotel operating model” that could result in major cost savings. Host executives have mentioned eliminating front desk staff, reducing restaurant offerings, and doing away with daily room cleanings as part of reexamining minimum “base labor standards.”

Host did not respond to requests for comment.

In some ways, economic downturns give corporations both the impetus and the cover to restructure their workforces, said Randy Albelda, a recently retired economics professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

“It’s an old story in the United States,” she said. “Workers who have essentially scratched their way up, and corporations that have the upper hand in terms of holding the power to hire and fire and to negotiate wages.”

Several hotel companies, including Marriott and Hilton, have already ended automatic daily housekeeping services at many properties — a practice that, if implemented industrywide, would slash the room attendant workforce by up to 39 percent, according to estimates by Unite Here, the national hospitality workers’ union. Carlos Aramayo, president of Unite Here Local 26 in Boston, which has been helping the non-union Marriott Copley workers, said this push to streamline staffs will not only lead to fewer jobs, it means the workers who remain could have more work piled on them.

One woman who still works at the Marriott Copley said that the hotel is so shorthanded that some employees are being asked to work six days a week. Workers are also on “pins and needles” about getting fired, said the woman, who asked not to be identified to protect her job security.

“I’m afraid because it might happen to me,” she said. “The managers are saying we’re safe, but look what they did to the other workers.”

Even before the COVID crisis, hotels had been seeking to cut labor costs as they fought off increased competition from home-sharing companies like Airbnb, said Isaac Wanasika, a management professor at the University of Northern Colorado, and properties are now focused even more on “reducing the human footprint.” A number of other local hotels got rid of workers during the pandemic, with no guarantees they’d be rehired, including the Revere and the Quincy Marriott. (The Four Seasons and Nine Zero also terminated staff, but later agreed to recall them when business returned.) A number of hotels around the country have also permanently reduced their staffs, including the Marriott Marquis in New York, which ousted 850 employees and is outsourcing its restaurant and catering operations.

Some who were let go from the Marriott Copley see a disconcerting pattern in the people hired to replace them. The five concierge lounge attendants, all immigrant women ranging from age 50 to 70, including Torres, filed complaints with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination for “age, race, and nationality discrimination” after they applied for and were rejected for jobs at the hotel’s new M Club lounge, jobs they said the general manager had told them before the pandemic would be theirs. Of the nine people hired to work there, all of whom previously worked at Champions, seven are white, according to the complaint, while their age range skews just slightly younger, from mid-30s to mid-60s.

“We were all immigrants and people of color, but they chose to make their lounge attendants younger and whiter,” said Patricia Tchoumi, 53, who is from Cameroon and made $23 an hour at the Marriott Copley, where she worked for 17 years.

Tchoumi just started orientation as a room service attendant at the Boston Omni Hotel at the Seaport, which opened last week. Her hourly wage is far lower than before, though she’ll also get tips. But she doesn’t know if she’ll get full-time hours; last week, she only got 15. Tchoumi is anxious to catch up on the mortgage at her three-family home in Lynn, where her unemployed tenants have been unable to pay rent.

Aside from the M Club staffers, it appears that most of the 50 Champions workers have not been rehired. The Yard House did not respond to questions about bringing back hotel staff.

Ramona Pena, 59, was a cook at Champions for 16 years, and has yet to find another job. She’s been applying in restaurants and stores, but worries that her age and limited English are holding her back. Her fiance also worked at the Marriott Copley, in security, but has been out on disability. Their hotel jobs allowed them to buy a house in Taunton in 2015, but now that her unemployment has run out, Pena, who is originally from the Dominican Republic, is worried about how they’ll pay the mortgage and support her parents.

When she found out she was being let go, she felt betrayed. “I felt it in my stomach, in my head. I still feel bad,” she said in Spanish through a translator, starting to cry. “I was definitely planning on working there until I retired.”

Labor advocates decry the outsourcing of staff jobs, noting that it allows companies to shift responsibilities to outside contractors and makes labor standards more difficult to enforce. But the immediate payoff is hard for companies to resist, said Wanasika, the University of Northern Colorado professor. “Outsourcing is an effective short-term strategy to reduce costs and risk,” he said.

Tahira Dzindo, a hostess at Champions for 14 years, came from Bosnia in 2001 with her husband and two young children and two backpacks, part of a wave of refugees fleeing the war torn country. They spoke no English and had no money, but Dzindo, 45, and her husband got jobs and eventually bought a house in Malden and put their daughter through college. “I was working double shifts,” she said. “Double, double, double to make as much as I could.”

No one called Dzindo about working at the Yard House, and she didn’t bother applying, considering hostess jobs are listed at $16 an hour — $8 an hour less than what she made there.

“That’s not going to get me anywhere,” said Dzindo, who is one of the lucky ones, recently landing a hostess job at a hotel restaurant making slightly more than she did at Champions. “[People] want to work, but they don’t want to work for nothing.”

Katie Johnston can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @ktkjohnston.